The history of a grand manor home

The very presence of historic homesteads in country regions reminds us of the halcyon days of agriculture, echoing tales of past triumphs and tragedies. In every district there are pockets of grandeur in unexpected places, built for the most part during the nineteenth century and reflecting those glory days.

The wealthy pioneers wanted their success clearly displayed in their grand homes, with no expense spared in creating ornate carved balustrades, cedar doors and skirting, decorative ceilings, cast-iron lacework and marble fireplaces, most of which made the long journey from mother England. In stark comparison, the servants’ accommodation, stables and outbuildings were utilitarian, following the standards of the time, and a rare number have survived the inevitable fate of a devastating fire.

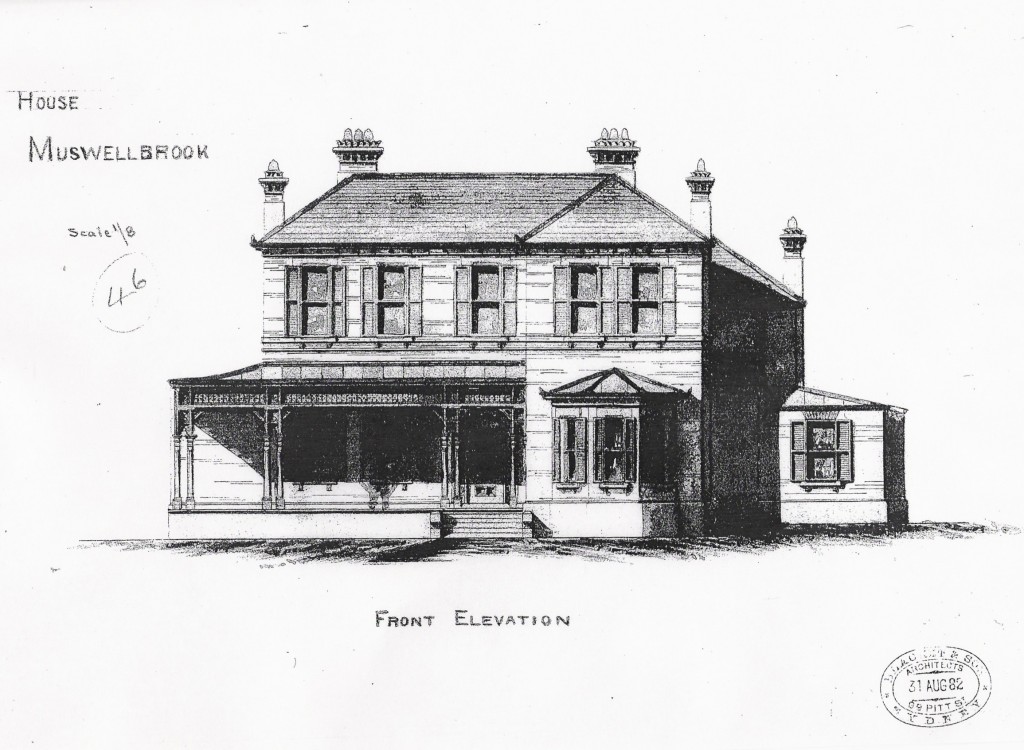

One notable residence in Muswellbrook, on a hilltop on the outskirts of town, is “Skellatar House”, circa 1883. Once grandly positioned on 3000 acres, over its colourful life the community has encroached on its perimeters as a result of subsequent subdivisions, and the estate is now two acres. But Skellatar House still commands a regal presence and is a reminder of the grandeur of yesterday.

Yvonne and Granville Taylor fell in love with the property at first sight, and since taking ownership ten years ago they have lavished much love and money on its exterior preservation by repainting and recreating gardens, adding to the extensive and heritage-sensitive internal restoration carried out by the previous owners.

The couple has become engrossed with the history of the property and has documented copious notes from the home’s onset and through the decades, realising the strong connection “Skellatar House” has with the town’s history.

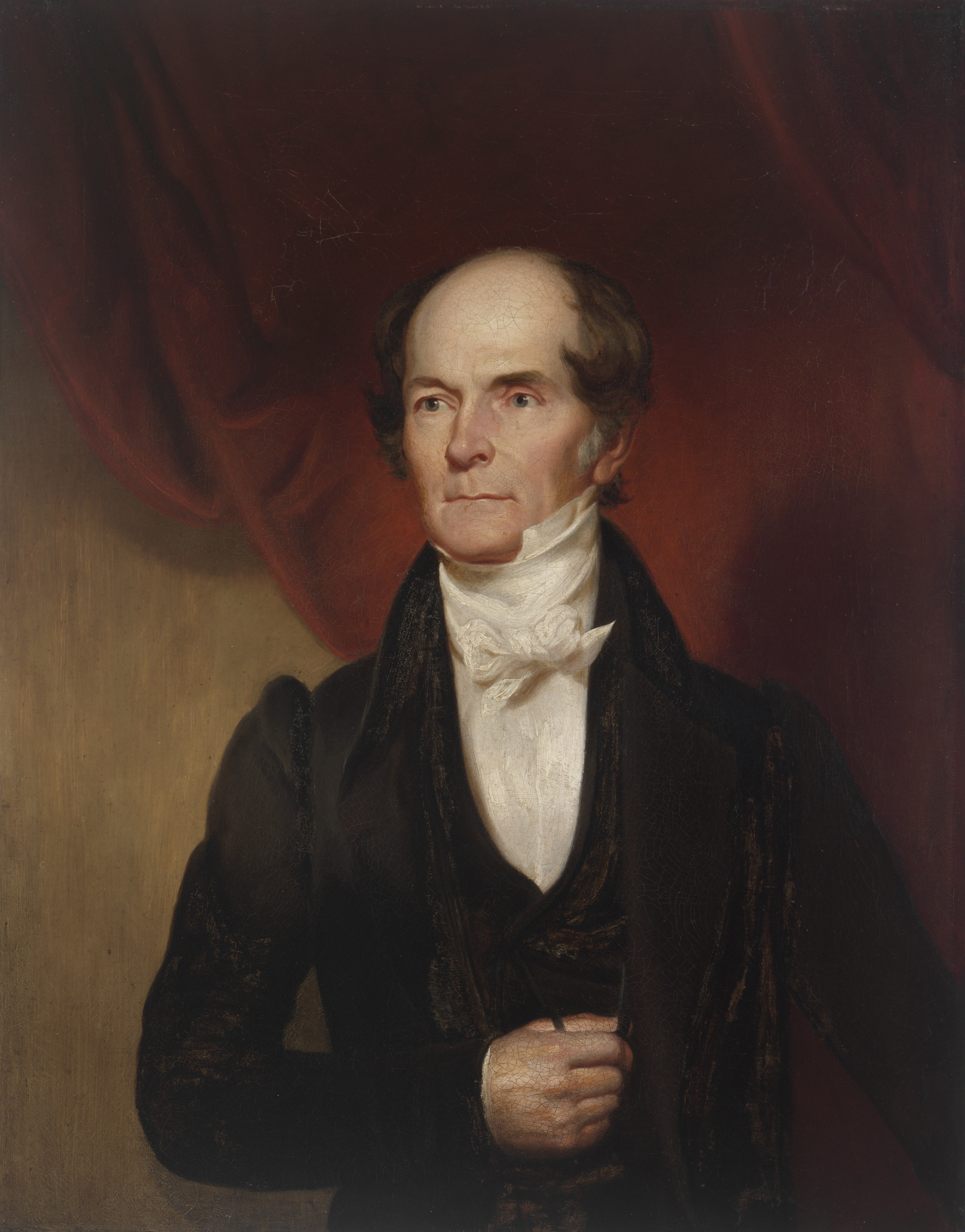

The earliest link dates back to the first Chief Justice of NSW, Sir Francis Forbes, an important figure in early colonial judicial history, responsible for converting the legal system of New South Wales from that of a penal colony, with total legal power vested in the Governor, to that of a free settlement. Sir Francis received land grants in the Muswellbrook area from Governor Darling, and purchased further parcels of adjoining land.

The resulting Skellatar estate, named after the Forbes family’s ancestral estate in Aberdeen, Scotland, was used for sheep and cattle grazing. After Sir Francis’ death in 1841 the estate was the subject of a mortgagee sale, leaving his widow penniless.

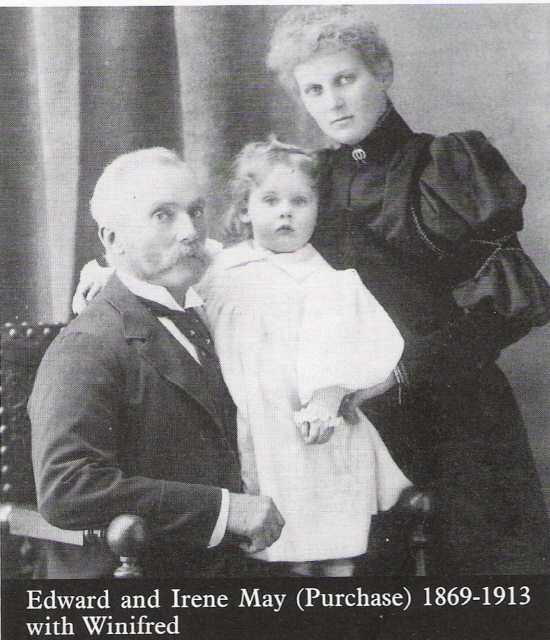

It was acquired by the wealthy Bowman family, of which George Bowman of Richmond was the patriarch, and in 1848 the property was divided between William Bowman and his twin brothers Andrew and Edward, the eighth and ninth sons of George Bowman born in 1840.

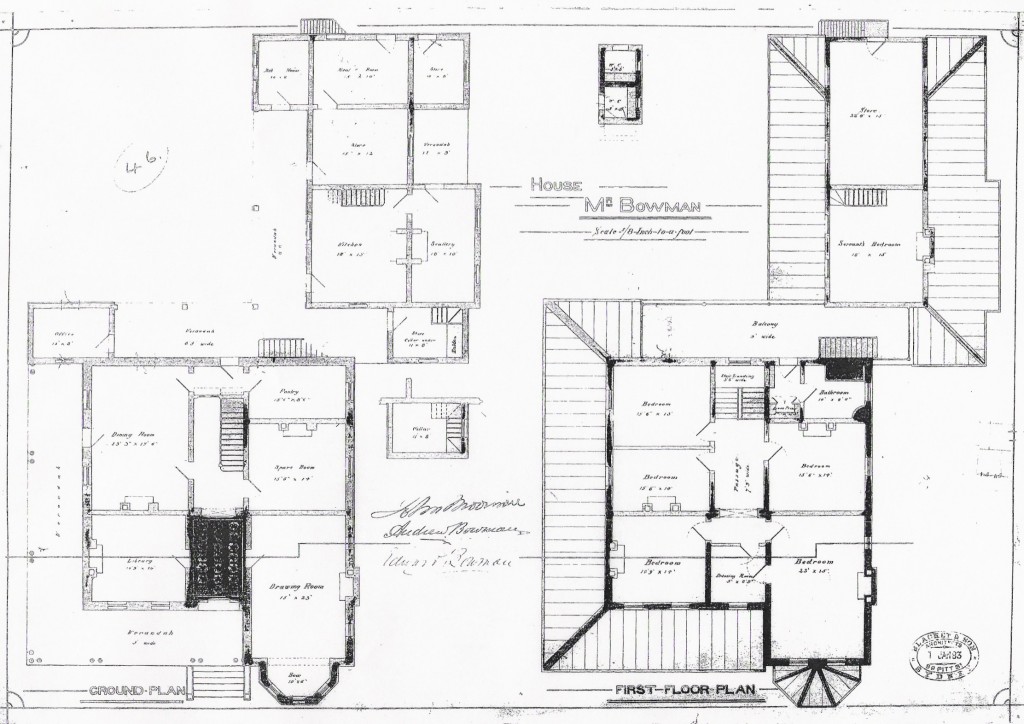

In 1881 Andrew and Edward Bowman, now both lawyers, commissioned Edmund Blacket, the third colonial architect of the day, and his son Cyril, to work on the plans to build a grand manor home on their portion of the estate.

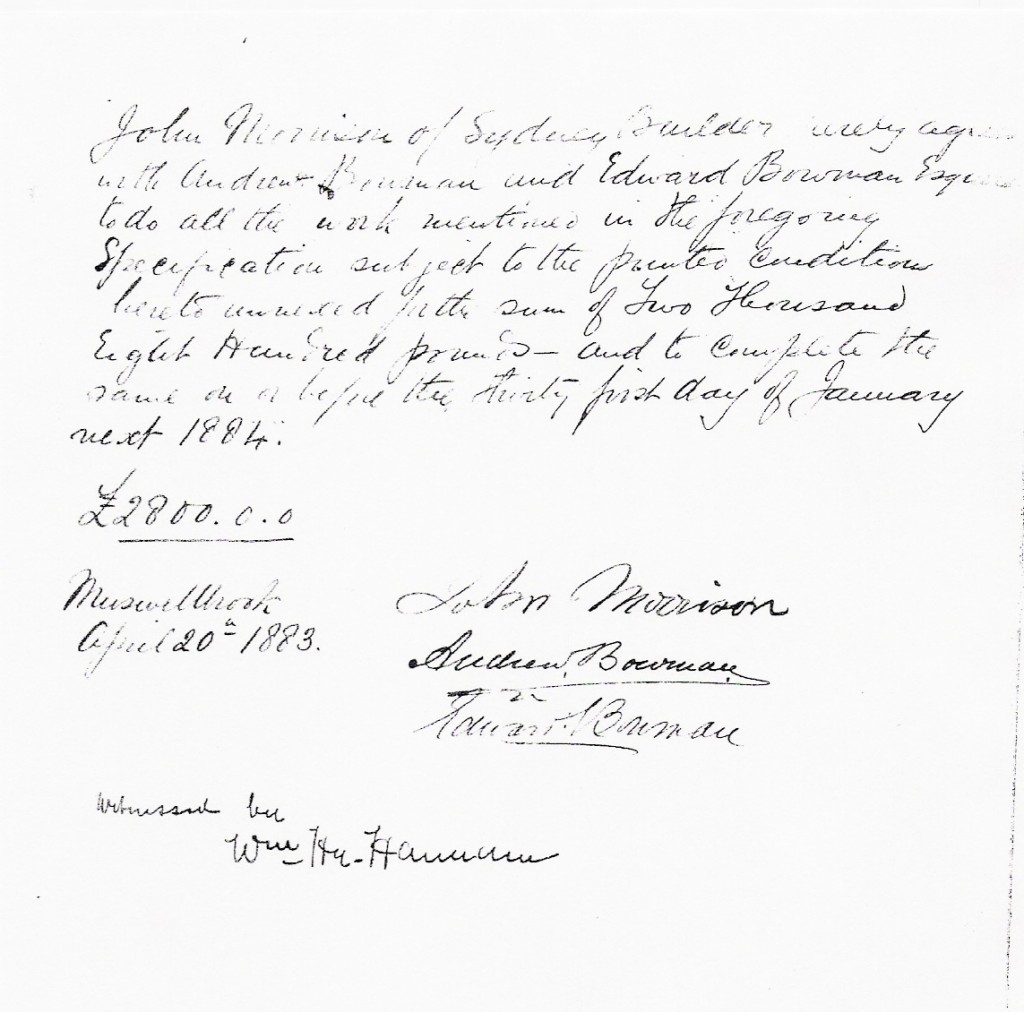

Working documents uncovered at the Mitchell Library show the contract price for building, by John Morrison of Sydney, was 2,800 pounds, excluding materials to be supplied by the Bowmans. The plans for Skellatar House are featured in a book titled “The Blackets: An Era of Australian Architecture” by Morton Herman.

The very existence of three stages of detailed plans, plus twenty pages of handwritten building specifications as well as the building contract, combine to form an abundance of research material for the owners, and for anyone interested in the history of architecture and building practices of the 19th century.

Edward was an alderman at Muswellbrook for 22 years, and Mayor for six terms (1875-1901). He was the first president of Wybong Shire Council, a magistrate, and First Lieutenant in the Muswellbrook Corps of NSW Volunteer Infantry. On his death in 1926 his only son inherited the estate.

Hunter Bowman died in 1952 and the property was subdivided into a number of parcels.

Skellatar Homestead and the surrounding 650 acres were purchased by the Catholic Church at an auction. The parish priest renamed this portion “Mount Providence”, a name which still survives as the retirement home on Tindale St., near Skellatar House.

In 1953 St Mary’s High School for Girls was established in the homestead, with an enrolment of 18 pupils under the tuition of the Sisters of Mercy.

In the 1960s the demands of the school curriculum called for such additions as a science block (now a garage and workshop) and in 1968 most of the pupils were transferred to St Catherine’s High School at Singleton and the school was forced to close.

The Catholic Church remained the owner, using the building for various purposes, including a temporary chapel for Mass, and a classroom for infant students of St James until the new school was completed nearby on part of the original estate.

Many local residents have fond memories of their school days at Skellatar House, either attending for their education, ballet classes or pre-school play groups.

The house has now been privately owned since 1997, as a family home. The main rooms boast seven marble fireplaces and 14ft ceilings, and there are wide architraves and skirtings and an imposing main staircase, all of Australian red cedar.

The Taylors have adapted for wine storage the original underground cellar with brick floor, accessed down well-trodden timber stairs from what is now a laundry room. Wide verandahs surround both storeys on all sides, and there are extensive outbuildings, external security lights and internal security and communication systems.

The kitchen has been tastefully modernised to today’s standards and the adjoining butler’s pantry, with cedar-lined ceiling and timber floor, is used for informal meals.

The stately formal dining room accommodates a ten-seater dining table and various sideboards with ease, and diners can choose to retire to the formal drawing room or the cosy informal sitting room.

The ground floor also boasts a book-lined library and a stately ballroom with an impressive stone fireplace. A small powder room completes the downstairs facilities.

The upper level accommodates the master bedroom with en suite, four guest bedrooms, main bathroom with claw foot bath, an additional bathroom with spa tub, and a legacy of days gone by – the small servants’ bedrooms now used as a sewing room and a study, atop an internal back staircase leading downstairs to the kitchen area. If only walls could talk!

Yvonne and Granville Taylor have delved into the home’s history and recorded a comprehensive factual account of its life. “Every day there seems to be someone else who can provide more information, having had some connection with one of the many lives of the property,” they say.

Whether by chance or purpose, views from the corner verandah look down along Bridge Street, the main street of Muswellbrook, as if the home is casting a watchful eye over the township, much as it has for the past 130 years.

Thank you to Marilyn Collins of Hunter Lifestyle Magazine for permission to reproduce this article.